Michael F. Cannon

Blue states are learning that it’s sometimes better if public health doesn’t come from the national government. The New York Times reports:

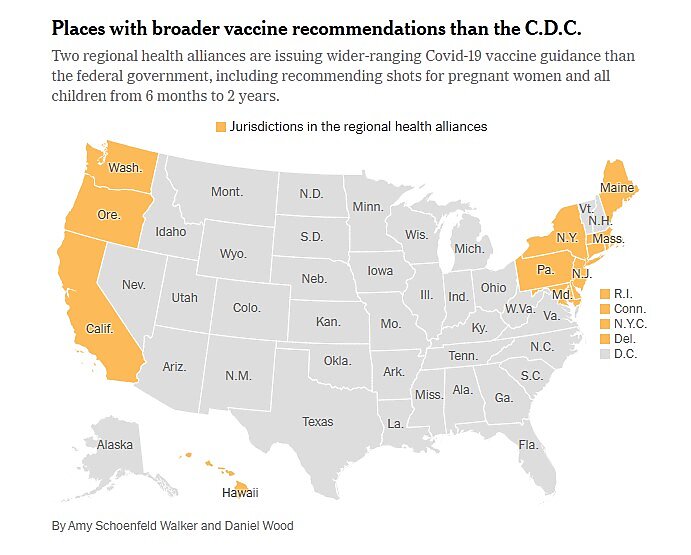

New York and several other Northeastern states are forging a regional public health coalition to issue vaccine recommendations and coordinate public health efforts in a rebuke to the Trump administration’s shifts on health policy.…

The effort is similar to the West Coast Health Alliance — a bloc of four Democratic-controlled Western states, including California — that issued its own vaccine guidance this week.

In “Public Health As If People Mattered,” in the journal Social Philosophy & Policy, I explain that subsidiarity is a crucial part of optimal public health strategy:

The considerable uncertainty about [public health] questions and trade-offs is a function of both the uncertainties inherent in health and medicine and in trying to maximize the “good” of autonomy without benefit of a functioning price mechanism.

It is because of these uncertainties that a key criterion of a violence-minimization framework is subsidiarity. That is, government responses to public health crises should always come from the most local level possible.

Nationwide or even multinational public health interventions may sometimes be beneficial because a contagious disease may spill over from one locality or one state to another. Smallpox eradication is an example of a sensible global public health strategy. When case rates are dramatically lower in some states or in some localities than in others, however, it makes little sense to have a national policy on masking or closures of schools and businesses.

Subsidiarity reduces the likelihood of government officials introducing coercion where it is not necessary. State and local officials generally have better information about their constituents’ needs and fewer forces diverting them from those needs than do officials of the national government. They also have greater incentive than national governments to tailor public health policies to minimize violence in their state. By contrast, nationwide policies can introduce unnecessary coercion in some states while simultaneously failing to address preventable private coercion in other states. A clear example of subsidiarity and its benefits is the FDA’s (perhaps reluctant) decision to allow states to certify COVID-19 diagnostic tests themselves.

Subsidiarity can also lead to better public health interventions. As states and localities experiment with different interventions, they can learn from each other’s successes and failures. Nationwide interventions do not create the same opportunities for competition and learning.

(Full article available on request.)

Blue states are doing essentially what red states did during the COVID-19 pandemic. Back then, a backlash against what many considered excessive federal controls led red states to reassert their public health preferences. Today, blue states are reasserting their public health powers and preferences in the face of what they consider too little action at the federal level.