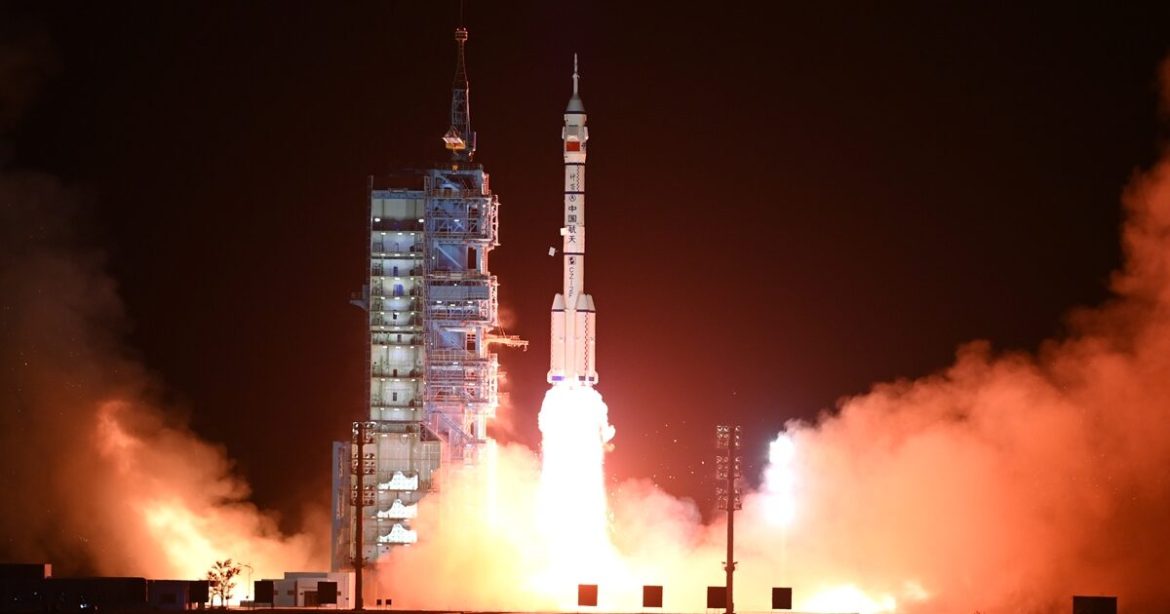

China opened its 2026 launch schedule on January 13 with two orbital missions. A Long March 6A rocket lifted off from Taiyuan carrying the Yaogan-50 (01) satellite into a highly retrograde orbit with a 142-degree inclination. Such orbits sacrifice launch efficiency but provide faster ground-track coverage and repeated access to mid-latitude regions.

While Chinese authorities described the satellite’s purpose in civilian terms such as land surveys, crop estimation, and disaster monitoring, Yaogan spacecraft are widely understood to support military reconnaissance, including radar, optical imaging, and signals intelligence. The highly retrograde orbit is notable because it requires significantly more fuel yet provides specific operational advantages such as enhanced coverage patterns or counter-surveillance benefits.

About an hour later, a Long March 8A rocket launched from the Hainan Commercial Space Launch Site, deploying nine satellites for the Guowang low Earth orbit megaconstellation. This marked the 18th Guowang launch, bringing the total number of operational satellites to 145, with plans to reach 400 by 2027 as part of a constellation ultimately envisioned at 13,000 satellites. Guowang is China’s state-led response to Starlink and is believed to support communications, navigation, remote sensing, and space situational awareness. China has filed plans with the International Telecommunication Union for future megaconstellations totaling more than 200,000 satellites.

Launching from Hainan reflects a strategic shift away from legacy military spaceports toward commercial infrastructure designed for frequent, high-density launches. The Long March 8A, optimized for aggregated satellite payloads, provides the lift capacity required for megaconstellation missions and supports China’s move toward reusable launch vehicles, following the December 2025 debut of the Long March 12.

These launches marked China’s 624th and 625th Long March flights overall. While the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation has not released a formal annual launch plan, projections suggest China could conduct more than 70 launches in 2026, potentially exceeding 100 when commercial rockets are included. This would represent an acceleration from 2025, when the country carried out 73 state launches and 92 launches overall, deploying more than 300 spacecraft.

China is extending its Belt and Road global infrastructure model into space by building and operating satellite ground stations, tracking facilities, and related infrastructure across Africa, Latin America, and the broader Global South. Rather than focusing solely on launches, Beijing is embedding itself into national space ecosystems by offering bundled packages that include satellite design, manufacturing, launches, training, and ground infrastructure.

A report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies finds that this approach has allowed China to integrate itself into dozens of national space programs. Chinese-built or operated facilities in countries such as Ethiopia, Egypt, Namibia, Venezuela, and Argentina now form a global network that strengthens China’s ability to track, communicate with, and control satellites worldwide. The geographic spread of these facilities provides redundancy that would be critical during a crisis.

Matthew Funaiole notes that much of this infrastructure is dual-use, capable of supporting civilian research while also enhancing China’s national security and military capabilities, with limited transparency over data control. A new China Space Cooperation Index shows that more than three-quarters of Beijing’s space partners are in the Global South. Once countries are integrated into China’s space ecosystem, disengaging becomes costly.

U.S. officials warn that China’s expanding on-orbit activity reflects a deliberate strategy to become the world’s leading space power, with space now viewed alongside land, sea, air, and cyberspace as a potential arena for conflict. According to U.S. Space Force assessments, China has met or exceeded most objectives set under its latest five-year plan, including advances in satellite communications, remote sensing, on-orbit artificial intelligence, and proliferated constellations. With more than 1,300 satellites already in orbit, China is testing stealthy satellites, ship-detection capabilities, and increasingly complex orbital behavior.

U.S. officials describe a shift from a cat-and-mouse dynamic in geostationary orbit to a hide-and-seek environment in low Earth orbit, as Chinese satellites increasingly rely on commercial platforms to observe U.S. space assets.

China’s space advances are unfolding in parallel with broader military technology developments. According to the U.S. Department of Defense’s 2025 China Military Power Report, flight testing of two sixth-generation aircraft prototypes began in December 2024. These include the Chengdu J-36, a heavy trijet flying-wing design, and the Shenyang J-50/XDS, a smaller twin-engine variant. Multiple prototypes flew in 2025, incorporating refinements such as thrust-vectoring nozzles and improved air intakes.

These aircraft are intended to support next-generation air superiority missions, including manned-unmanned teaming and potential carrier operations, with an expected operational timeline around 2035. Complementing these developments, the KJ-3000 airborne early warning and control aircraft, based on the Y-20B platform, conducted its maiden flight in 2024. The aircraft features advanced digital radar, possibly Gallium Nitride-based, offering improved anti-jamming performance, stealth detection, passive sensing, and target identification. It is designed to augment existing systems, including upgraded KJ-500 platforms and the carrier-based KJ-600.

Analysts expect China to demonstrate more advanced space capabilities in 2026 as strategic competition increasingly extends beyond Earth’s atmosphere. Anticipated developments include on-orbit refueling tests, mobile geostationary satellites with unclear missions, AI-based space computing enabled by the Three-Body Constellation, and initial attempts to recover reusable rocket boosters.

Planned missions for 2026 include crewed Shenzhou flights to China’s space station, the debut of the Long March 10A heavy-lift rocket, and the Chang’e-7 mission to the lunar south pole.

The post China’s Quest for Space Supremacy in 2026 appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.