Tad DeHaven

The recent port strike by the International Longshoremen’s Association was suspended after dockworkers received a massive pay increase. However, the union’s opposition to port automation technology on job preservation grounds remains the major sticking point to the union accepting a new contract by a January 15 deadline.

As I previously discussed, worker opposition to labor-saving technology is hardly new. In the short term, new technologies can cause job losses in the affected industry. That was the result of the introduction of shipping containers in the mid-20th century. In the long term, technology enhances productivity and thus fosters higher living standards, better wages, and more jobs in the broader economy. That was also the result of containerization.

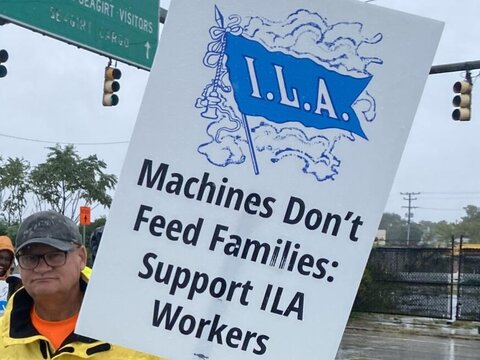

Striking dockworkers on the picket line often held up signs that said, “Machines Don’t Feed Families.” The sentiment is understandable from the view of a dockworker concerned that automation could lead to the loss of his job. Alas, it simply isn’t true, and we need only look at the US agriculture industry to see why.

According to US Census data, farm workers accounted for 38 percent of the US labor force in 1900. Today, that figure is about 1 percent. As the following chart shows, the number of farm workers dropped precipitously over the course of the 20th century.

A US Department of Agriculture article explains what happened:

The decline in farm labor occurred as workers sought higher wages and other income opportunities in the nonfarm sector, especially after World War II. In addition, the transformation of the farm structure toward fewer and larger farms and the development of labor-saving technologies—such as bigger and faster tractors and combines and automated feeding equipment—reduced demand for farmworkers.

Farmworker employment plummeted but total US agricultural output soared. That’s because total factor productivity—the amount of agricultural output generated by a combination of land, labor, capital, and resources—soared. Thanks in good part to the mechanization of labor-intensive work, a growing population came to enjoy an abundance of food, and workers who left the farms eventually found new and better-paying jobs.

A McKinsey & Co. study notes that farm automation is still in its infancy, but that a combination of higher resource costs and sustainability pressures from regulators and customers should lead to greater adoption:

Automation can help reduce these costs by enabling farmers to use pesticides and fertilizers more efficiently. For example, automated precision spraying enabled by sensors and field data (both stored and in real time) can sense gaps between crops and adjust the volume and timing of chemical sprayed accordingly, using fewer chemicals. Some herbicide application technologies use computer vision to selectively spray weeds and avoid crops. On large US corn farms, these solutions have been shown to reduce herbicide costs by 80 percent, creating a value of $30 per acre and a payback period of two years. Similarly, fertilizer application robots enabled with sensors can control the amount of fertilizer that is directly applied onto individual seeds during the planting process. This can save more than 93 million gallons of starter fertilizer annually across US corn farms alone.

In addition to efficiency gains in terms of profit, automation could protect workers from exposure to chemicals and reduce negative impacts on the environment.

That would be progress in every sense of the word.

My colleague Chelsea Follett recently wrote about the “Horrors of Pre-Industrial Farming,” which demonstrates that even farm animals would be relatively better off. Her depiction of late 18th century conditions for dairy cows in London and the “blue milk” they produced is unfathomable in today’s world. In contrast, the following video shows the amazing machines used in a modern dairy, including automated brushes that “allow cows to scratch themselves whenever they need.”

In “What Buc-ee’s Can Teach Us About the Port Strike,” Scott Lincicome explains that the disagreement between shippers and dockworkers “isn’t just with automation; it’s with productivity more broadly and US ports’ woeful, economically damaging performance in this regard.” Using the grandiose Texas gas station chain as an example, he demonstrates how Buc-ee’s is “a story of labor productivity, what drives it, and how it benefits both consumers and workers alike”:

It boasts the world’s largest convenience store and world’s longest car wash, and each Buc-ee’s outlet features in-house barbecue brisket stations, 100-plus gas pumps, sparkling-clean restrooms, and… ridiculously good pay. As indicated in the table below—and as constantly featured online—the lowest-paid workers at most Buc-ee’s locations make an impressive $18/hour, while managers can rake in $100,000 a year or more (much more). And all positions come with benefits, paid vacation, and even 401(k) matching.

I couldn’t find detailed information on the equipment Buc-ee’s uses to prepare its smoked brisket other than it’s done at an offsite smokehouse. However, regardless of how rudimentary, any device that uses mechanical principles to cook food by indirect heat and smoke is a machine. So, once again, machines do feed families.